Dynamic Functionality with Vanilla JS

Let’s imagine that we want to implement a menu that we can toggle. We might write the JavaScript code like this:

const menuToggle = document.getElementById("menu-toggle");

const menu = document.getElementById("menu");

const toggleMenu = () => {

menu.classList.toggle("open");

};

menuToggle.addEventListener("click", toggleMenu);This code assumes that there are elements with the ids of menu-toggle and menu on our page. If, for example, the menu element is not there, the script crashes and everything after the fifth line doesn’t get executed.

This works both ways, our script needs to be aware of the markup and our markup also needs to be aware of the script. The HTML needs to know what ids are expected for the menu to work. This means that by changing either the HTML or JS, we can accidentaly break the menu.

Another problem is that if we have multiple toggles on our page, we need to change the logic of selecting them and adding event listeners.

You can see that even though it’s a very simple example, the markup and logic are tightly coupled, despite the script being in a separate file.

Manipulating the DOM

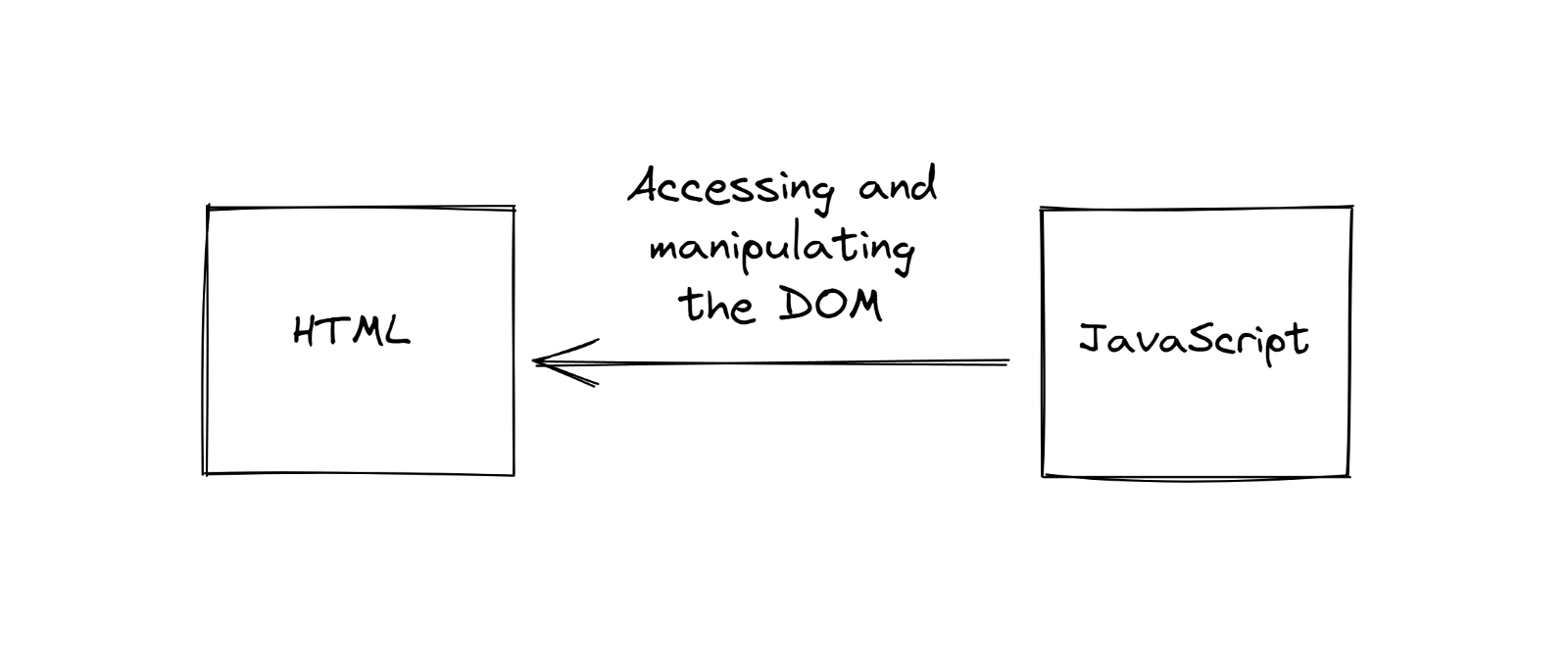

Traditionally, when adding dynamic functionality to a website, we define some static HTML or a template then we try to access the DOM with JS to manipulate it:

This is problematic because the HTML is not aware of the script. Adding dynamic functionality to it is hard because we have to make a lot of assumptions about the document’s structure.

Reversing the flow of rendering

JavaScript frameworks fix the above problem by allowing the developer to render all of the HTML using JS, be it using JSX or templates. Here is the menu example written using React:

const useToggle = () => {

const [isOpen, setIsOpen] = useState(false);

const toggle = () => setIsOpen((prev) => !prev);

return [isOpen, toggle];

};

const Menu = () => {

const [isOpen, toggle] = useToggle();

return (

<>

<button onClick={toggle}>Toggle menu</button>

<div className={isOpen ? "open" : ""}>Menu goes here</div>

</>

);

};Instead of writing static HTML and trying to slap interactivity on top of it, we define the logic, then we render the markup which is able to make use of that logic.

This way we’re getting rid of the implicit dependecy between the JS and HTML and the ambigiuity surrounding it. If our markup needs some data, we need to provide it.

Notice that we’re still able to separate the business logic from the HTML. In fact, it becomes easier than before because the framework abstracts away the DOM updates for us. However, we keep the rendering logic - applying the class name - in the markup, which is how it’s done in any HTML templating language.

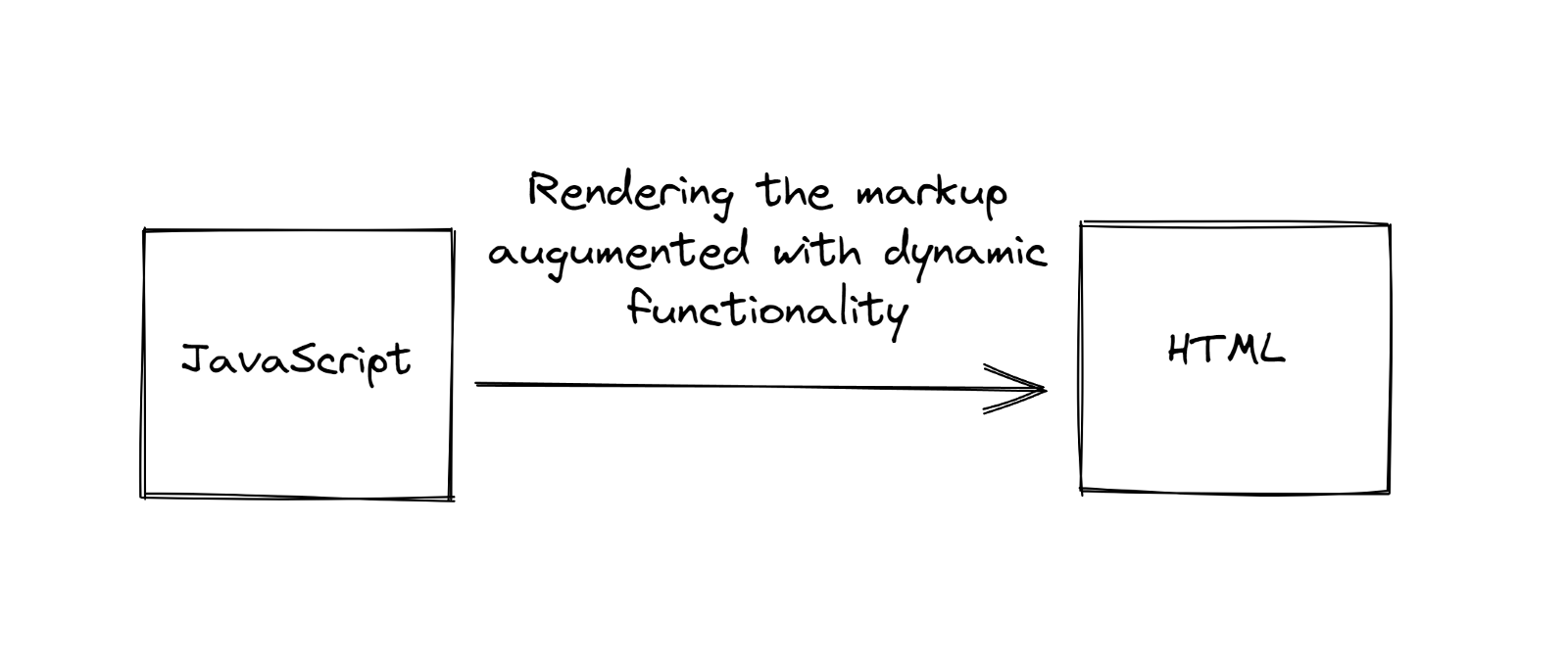

The flow of rendering here goes something like this:

This removes the burden of having to select elements on the page to do stuff with them because we already have the event listeners and state variables available to us when rendering the markup.

Now you might be thinking, what if we rendered our HTML with vanilla JS? It’s possible but we would still need to select DOM nodes after the initial rendering to update them. We’d end up with a mix of declarative and imperative code. If we wanted to make the rendering code the single source of truth for our markup, we would need to come up with a way to replace the elements when the state changes, or create a compiler to write the DOM updating code for us. At this point we’re building our own inefficient JavaScript framework.